Grad school provided me with a lot more insight into the problem of gender inequity than I bargained for. While I was pursuing a PhD in economics — a highly gender-imbalanced discipline, with women accounting for 12 percent of American economics professors and only one female Nobel prize recipient to date — my partner was immersed in Ada Developers Academy. Ada is an intensive training program for women who want to become software engineers.

Part of her training included discussions about the various ways that sexism exists and persists in the technology sector, which is only slightly less gender-imbalanced than academic economics. In conversations with her, I became aware of how rife graduate school was with many of the same dynamics that make tech an uncomfortable place for many women. The issues here are both deeper and broader than pay disparities, and data we gathered this fall supports the notion that even (and perhaps especially) highly educated women experience gender inequity in the workplace.

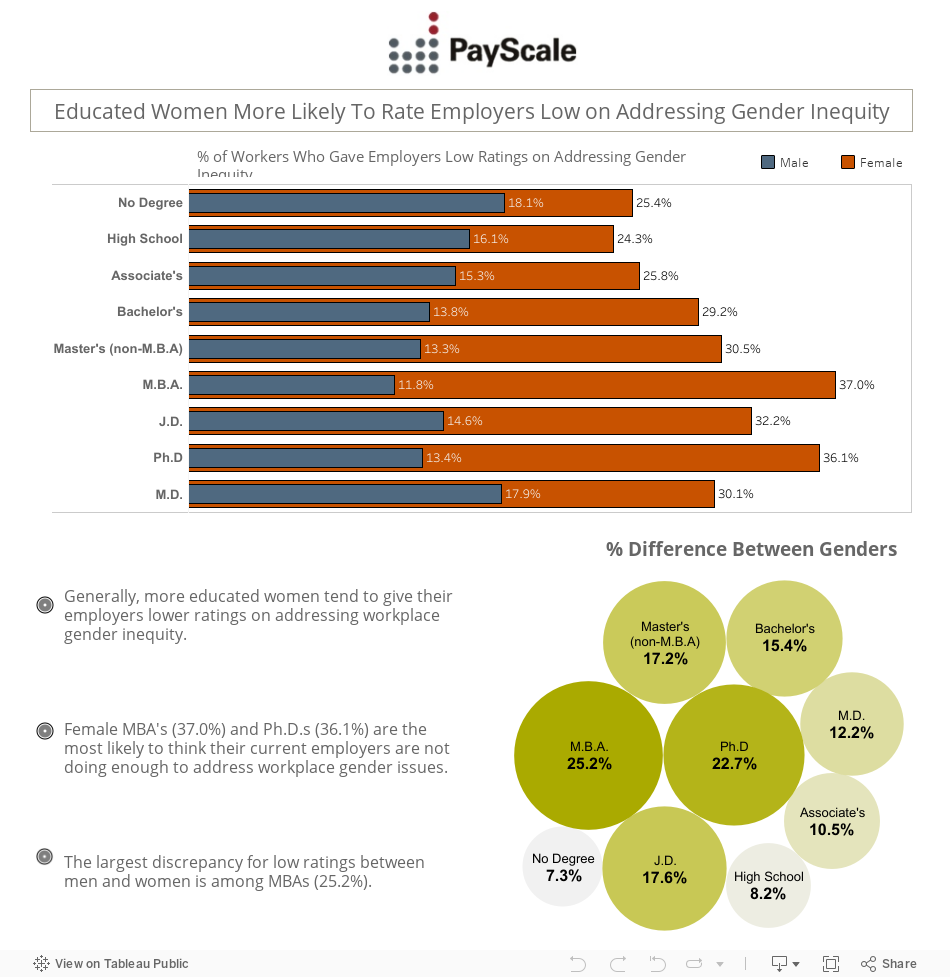

Educated Women Give Their Employers Low Marks for Gender Equity

When the research team at PayScale started preparing this year’s gender pay report, I wanted to determine whether highly educated women had different experiences of workplace gender inequity than men or women with different levels of training. To do this, we asked survey respondents to rate their employer’s activity regarding workplace gender inequity. They could choose a rating from 1 (“No action is taken”) to 5 (“My employer is proactively addressing the issue”). There was also a sixth response option: “There is no issue, so no action is needed.” When compiling this data for the report, we deemed either a 1 or 2 a low rating.

We found a disturbing trend in the data. As men gained more education, they tended to be less likely to give their employer a low rating in addressing workplace gender inequity. The opposite happened for women, however — highly educated women were more likely to report an unaddressed problem in the workplace.

This difference in experiences is most pronounced with MBAs. Male MBAs were least likely of any group to rate their employers poorly in addressing workplace gender inequity (11.8 percent), while female MBAs were most likely (37 percent).

This is troubling. Some of the most capable women in the workforce believe that they are being judged on their gender rather than the quality of their work.

Why Do More Highly Educated Women Give Their Employers Such Low Marks?

I suspect there are at least two forces at play here: (1) as women spend more time in school they become more conscious of how their gender systematically disadvantages them; and (2) in positions requiring high levels of training and autonomy, the fact that women (and particularly women of color) are presumed incompetent until proven otherwise becomes more apparent. To put it differently, women with higher levels of education could be both more aware of gender discrimination and more susceptible to it. I want to focus on the second point in this piece.

The problems women face in universities show how pay is only one piece of the gender discrimination puzzle. Check out HASTAC’s excellent summary of recent work in this field. The first step in this body of research is describing gender issues. Are women entering fields at different rates than men? Are women in these fields remaining or dropping out? When we consider things like academic publications, are publication rates by gender in line with the gender makeup of the fields, or is men’s work more likely to be published in leading journals than women?

The second step is to explain why these patterns exist. If women are less likely to publish in leading journals, we want to know if it is because of “pure” sexism or some other explainable reasons. For example, are women more likely to leave the field early? Or, do women in a field tend to be younger, so more seasoned researchers are more likely to be male? When we report uncontrolled and controlled gender pay gaps, we’re following the same pattern of describing then explaining.

Academia: The Perfect Breeding Ground for Unconscious Bias?

I want to discuss one aspect of the academic world that makes women particularly vulnerable to discrimination. I think this applies to highly educated people regardless of where they end up working: the more advanced someone’s work, the more difficult it becomes to objectively evaluate that work.

Academic research tends to take place at the fringe of usefulness, and for good reason. We cannot know beforehand which projects may end up greatly advancing our understanding or having practical or policy application. Pure research is a risky gambit that sometimes pays off. Because so much of this research requires graduate training to understand, there is a relatively small group of people who can read and understand your work.

Your professional success as an academic depends on how this small group evaluates your work — is this good enough to satisfy the requirements for your thesis? How about for publication in a journal? The peer-review system attempts to anonymize this process for publications, which should remove gender bias. However, it doesn’t always work this way — you may remember this fiasco last year when a journal reviewer’s feedback suggested that female researchers add a male coauthor.

As a graduate student, access to advisors and resources in graduate school depends so much on an opaque process of professors deciding whether you’re “worth” the effort and time investment. Unconscious gender discrimination thrives in this type of decision-making — people’s gut instincts are shaped by their experiences with the individual and by a whole suite of beliefs they hold about the groups they think the individual belongs to.

Since we’re frequently left with subjective evaluations of advanced work, the door is left wide open to biases. Colleagues may be more likely to challenge or doubt a strategic decision from a female MBA than a male MBA, for example. Our data can’t speak specifically to the why, but it does show that highly educated women don’t think their employers are doing enough to address workplace gender inequity. Combine this with our finding that women who give lower ratings on gender inequity activity are more likely to be flight risks, and employers should be on notice.

Tell Us What You Think

How would you rate your employer on dealing with gender inequity in the workplace? We want to hear from you. Tell us your thoughts in the comments or join the conversation on Twitter.

Being a hands-on techie in Computing world, had always been mostly single woman in team. And all that I did was never enough, sometimes was openly told that what I did would have been done by my male counterpart in half the time, and still they are not complaining about it. Women get into Impostor Syndrome, and if cannot increase awareness, take to a ‘yes boss’ working style. Fighting such cold wars certainly takes toll on emotional and physical health.… Read more »